Exploring Fungi’s Billion-Year History

Author Merlin Sheldrake is the son of Rupert Sheldrake, the Cambridge theoretical biologist who constructed the morphic field theory. Rupert collaborated with psychedelic philosopher Terence McKenna and pioneer chaos mathematician Ralph Abraham as part of the Trialogues, legendary discussions that started at the Esalen Institute in California in 1989 and continued for a decade.

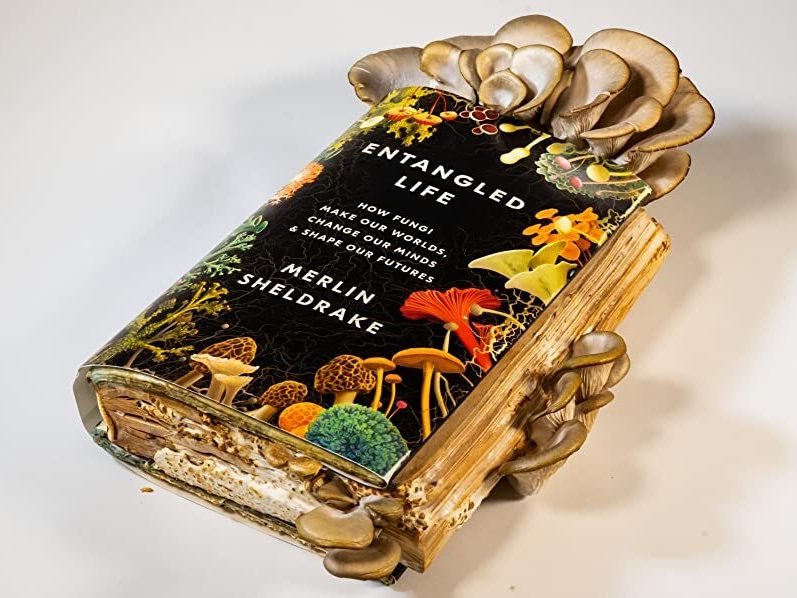

In “Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures,” Merlin Sheldrake writes that he learned at age seven, while vacationing with his family at the McKenna home in Hawaii, that certain plants and fungi can alter human consciousness. He has known the master mycologist Paul Stamets since he was a teenager. Sheldrake notes in the introduction that he was also a subject in a research trial focused on studying how LSD enhances the human creative potential and problem-solving capabilities.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Sheldrake received a Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge and deepened into his own life direction, focusing his doctoral work on underground fungal networks in tropical forests. His unique biographical history allows a deep understanding of this material.

Sheldrake takes the reader deep into the experience of fungal life, providing a digestible description of its biology and essential importance in our biosphere. He writes:

Fungi are everywhere but they are easy to miss. They are inside you and around you. They sustain you and all that you depend on. As you read these words, fungi are changing the way that life happens, as they have done for more than a billion years. They are eating rock, making soil, digesting pollutants, nourishing and killing plants, surviving in space, inducing visions, producing food, making medicines, manipulating animal behavior, and influencing the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere. Fungi provide a key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways that we think, feel, and behave. Yet they live their lives largely hidden from view, and over ninety percent of their species remain undocumented. The more we learn about fungi, the less makes sense without them.

Many pages are devoted to Sheldrake’s observations about the pervasive role of fungi, elegantly presenting mycelial structures, the large underground bodies of fungi. Mycelia can stretch for miles, connecting the root systems of plants in the environment which enables plants in the network to transfer resources and electrical information.

Sheldrake notes that the symbiotic relationship between plants’ roots and fungi is so evolutionarily entangled that plants could not exist without fungi, even suggesting that fungi were likely the first form of root systems that enabled plant life to develop on land.

The mycelial structures of fungi are so vast and complex, writes Sheldrake, that “some fungi have tens of thousands of mating types, approximately equivalent to our sexes…” and “The mycelium of many fungi can fuse with other mycelial networks if they are genetically similar enough, even if they aren’t sexually compatible,” widening the reach of these intelligent and relational webs.

Sheldrake notes that we keep discovering how fungi are more ancient than previously thought. In 2017, fossilized mycelial structures that formed 2.4 billion years ago were found; that is a billion years before fungi were previously believed to have evolved. The symbiotic relationship between fungi and plants originate at the dawn of their interaction, writes Sheldrake, and so does the relationship between fungi and animals, which share a common ancestry.

“Psilocybin was produced by fungi for tens of millions of years before the genus Homo evolved,” he writes. “The current best estimate puts the origin of the first ‘magic’ mushroom at around seventy-five million years ago.”

As someone who wrote a doctoral dissertation on psilocybin mushrooms, I found it refreshing and rare to see a scholar who focuses their doctoral work on ecological mycology discuss the evolution of psilocybin. Sheldrake observes that given its astounding impact on human consciousness, psilocybin and its evolution have been understudied. He writes:

Two studies published in 2018 suggest that psilocybin did provide a benefit to fungi that could make it. Analysis of the DNA of psilocybin-producing fungal species reveals that the ability to make psilocybin evolved more than once. More surprising was the finding that the cluster of genes needed to make psilocybin has jumped between fungal lineages by horizontal gene transfer several times over the course of its history. As we’ve seen, horizontal gene transfer is the process by which genes and the characteristic they underpin move between organisms without the need to have sex and produce offspring. It is an everyday occurrence in bacteria—and how antibiotic resistance can spread rapidly through bacterial populations—but it is rare in mushroom-forming fungi. It is even more rare for complex clusters of metabolic genes to remain intact as they jump between species. The fact that psilocybin gene clusters remained in one piece as it moved around suggests that it provided a significant advantage to any fungi who expressed it. If it didn’t, the trait would have quickly degenerated.

The evolutionary benefit of psilocybin for the fungi that produce it is still up for debate. Sheldrake observes that, “It seems probable that the evolutionary value of psilocybin lay in its ability to influence animal behavior.”

Sheldrake investigates in-depth how certain fungi affect animals, especially ants. He concludes that psilocybin likely didn’t evolve as a deterrent for insects and other animals, but instead as a lure, changing behavior in ways that benefits the fungus.

Sheldrake superbly presents the complexity of fungi for a public audience. His expertise and interest in the topic are palpable. He holds a deep understanding of the ecological web of life and contextualizes the importance of fungi in interconnected ecosystems, as well as showcasing examples of humans solving many contemporary problems with the assistance of fungi. Some of these solutions include healing infected bee populations, the cleaning of waste, and bringing mental health into greater wholeness. As Sheldrake writes,

“This sort of relationship-building enacts one of the oldest evolutionary maxims. If the word cyborg — short for ‘cybernetic organism’ — describes the fusion between a living organism and a piece of technology, then we, like all other life-forms are symborgs, or symbiotic organisms.”

“Entangled Life” intelligently expresses the nuanced symbiotic relationship between fungi and the planet, further deepening our understanding of the relationship between humanity and fungi.

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures By Merlin Sheldrake 368 pp. Random House. $28.

Image: Merlin Sheldrake