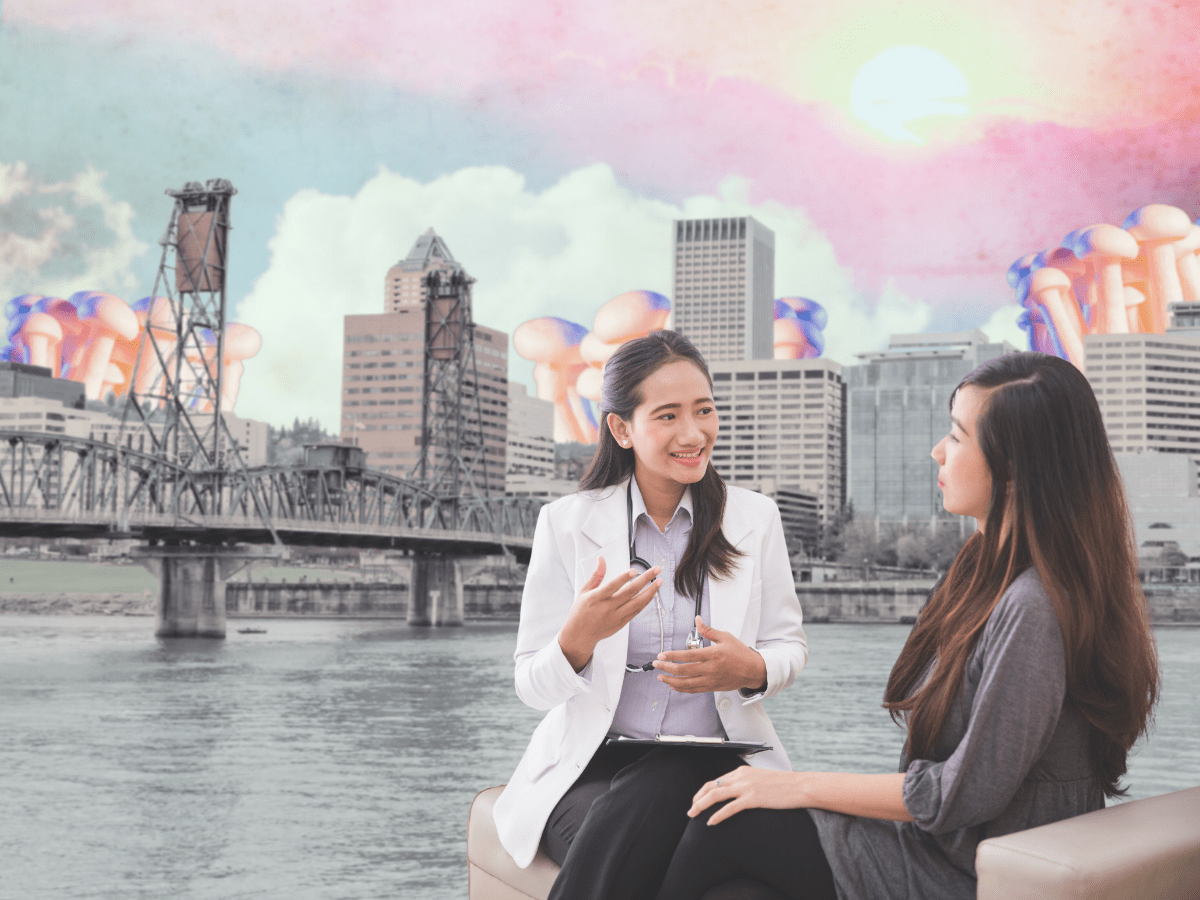

Psilocybin-assisted Therapy is Officially Legal in Oregon

Oregonians have spent two years since the passage of Measure 109 waiting while the rules for supervised adult use of psilocybin were thrashed out. The back and forth between the Oregon Psilocybin Services (OPS) branch of the state-run Oregon Health Authority (OHA) and the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board, which makes recommendations to state regulators, has finally concluded.

The OHA final rule drop took place on Dec. 27, 2022, four days before the absolute deadline. The OPS also added an open letter and a Hearing Officer Report responding to the more than 200 written comments and six hours of responses from live forums offered during the November 2022 public comment period.

State legalization of psilocybin in Oregon began January 1 and the OHA started accepting license applications for psilocybin providers on January 2. Facilitators and mushroom providers are required to be trained and earn their state licenses, however, before they can practice.

Most experts expect the first legal facilitated use of psilocybin to begin in late summer 2023. The OHA letter asserted that psilocybin service centers should offer information in Spanish as well as English and that all license applicants will be required to submit a social equity plan as part of their application. The OHA statement also addresses the use of sub-perceptual doses (microdosing), the pricey license fees ($2,000 for facilitators or guides, $10,000 for producers), personal data protection, and public safety.

The psilocybin entrepreneurs, lobbyists, medical professionals, enthusiasts and underground guides who staffed the five committees of the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board have had their say, and the Health Authority has listened. Lucid News asked a handful of local experts how they think the rollout of the rules is going.

Observations on The Rollout

Vince Sliwoski, a lawyer at the international law firm Harris Bricken and editor of the firm’s Psychedelics Law Blog, pointed out that the 200 public comments on psilocybin rule making submitted was “far from overwhelming.”

Sliwoski explained that this was consistent with “the phenomenon of interested parties having strong opinions about controlled substances programs (and government programs more generally), but declining to contribute to the record.” According to Sliwoski, the relative lack of comments about regulation also reflects “the fact that the regulated psilocybin industry in Oregon will be smaller than many people initially expected.” In other words, he believes that many in Oregon’s psychedelic underground are keeping their distance for now.

Other insights about the final rules that Sliwoski picked up on include the observation that outside parties still will not be allowed to be present when psilocybin is being administered. The rules about facilitators needing to call emergency services at the slightest sign of distress have also been loosened. “The rules have been amended to require service centers to adopt procedures for client emergencies, and to take mitigation steps prior to contacting emergency services,” said Sliwoski.

Mason Marks, a senior fellow, and lead of the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School, has also kept a sharp eye on Measure 109 from the beginning.

“If I had to grade Measure 109’s two-year implementation period, I’d give it a B minus,” he wrote in an email to Lucid News. “During the first year, the leadership of the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board invited too many friends and celebrity guest speakers to its meetings. Though these speakers were often interesting, they left little time for important board discussions and recommendations. After eight to twelve months, things improved, but the board was constantly making up for lost time.”

Marks also notes that he saw a lack of transparency around rule-making, and conflicts of interest as board members created rules that would affect their own future psilocybin businesses.

“Lobbyists and industry insiders shaped many aspects of the process behind closed doors. Despite Measure 109 being a non-medical psilocybin program, its implementation period was dominated by healthcare practitioners and their relatively narrow perspectives,” says Marks who asserts that Indigenous and religious views on psilocybin were largely ignored.

Marks also felt the public were cut out of the process, although all the Zoom meetings were open to the public, and periods of public comment were held.

“The board and the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) would occasionally listen to the public,” says Marks. But most of the time, regulators appeared to avoid engaging community members in dialogue.”

As a result of what he perceived as a lack of community input, Marks fears that the cost of psilocybin services in Oregon will be too high for average people.

“During the implementation period, more time should have been spent on affordability and access,” says Marks.

He noted, however, that the board members were committed to the hard work of fulfilling the process, and by year two, they became more focused and organized.

“Smart agency choices included creating clear boundaries between psilocybin services and Oregon’s medical facilities and services,” says Marks who said this has been a concern of many observers from afar. “Psilocybin facilitators cannot make medical claims, diagnose or treat health conditions, or operate within healthcare facilities.”

Marks also praised the last-minute allowance by the OHA for microdosing, which could be less expensive for customers and require less time for facilitation.

Data privacy and protecting client confidentiality, two of Marks’ hot topics, were also addressed by the OHA.

Marks hopes that other states that legalize psychedelics, such as Colorado, will “learn from Oregon’s missteps and successes.”

While he’s not the first white male in Oregon to call for more diversity, Marks says other jurisdictions should pay particular attention to creating advisory boards that do not perpetrate established power structures.

“Advisory boards should be far more diverse. Their members should do their homework and be prepared to hit the ground running. Conflicts of interest should be taken seriously from the start and play a significant role in board member selection and voting,” says Marks. “Members of the public and affected communities should be better integrated into the rule-making process, which should also be better insulated from lobbyists and industry insiders.”

For those in the trenches hoping to train facilitators and treat actual clients, Rebecca Martinez appears to capture the feeling of cautious optimism among those planning to provide psilocybin under the new rules.

“I don’t expect to have a perfect program on day one,” says Martinez, the founder and director of the Alma Institute in Portland. “I believe with active community involvement, we can move in the direction of health equity from the outset. I anticipate the first half of the coming year will be behind-the-scenes work to get up and running. I will be satisfied if we have several access-focused services sites open to the public by the summer of 2023.”